FOSDEM 2026 felt huge this year. I kicked off day one with Patrick Steinhardt’s session, “Evolving Git for the next decade”, and it was exactly what I wanted: a crisp, high-signal tour of the big changes already landing in Git, plus what’s being lined up for the next major era.

Patrick structured the talk around four themes:

- SHA-256 transition

- Reference storage (reftable)

- Large file management

- Usability improvements

Below is my write-up, with practical commands and links if you want to dig deeper.

SHA-256 transition: from “available” to “default”

Git has supported repositories that use SHA-256 object IDs since 2.29 version (as an alternative to SHA-1). The big shift isn’t whether it exists — it’s whether the ecosystem treats it as a first-class default. The goal: make SHA-256 the default choice in Git 3.0 so hosting providers, tooling, and integrations finally have to keep up.

To try it locally:

git init --object-format=sha256

Git has supported repositories that use SHA-256 object IDs since 2.29 version (as an alternative to SHA-1). The big shift isn’t whether it exists — it’s whether the ecosystem treats it as a first-class default. The goal: make SHA-256 the default choice in Git 3.0 so hosting providers, tooling, and integrations finally have to keep up.

To try it locally:

git init --object-format=sha256

A couple of reminders:

This is a repository format choice. Older Git versions can’t read SHA-256 repos.

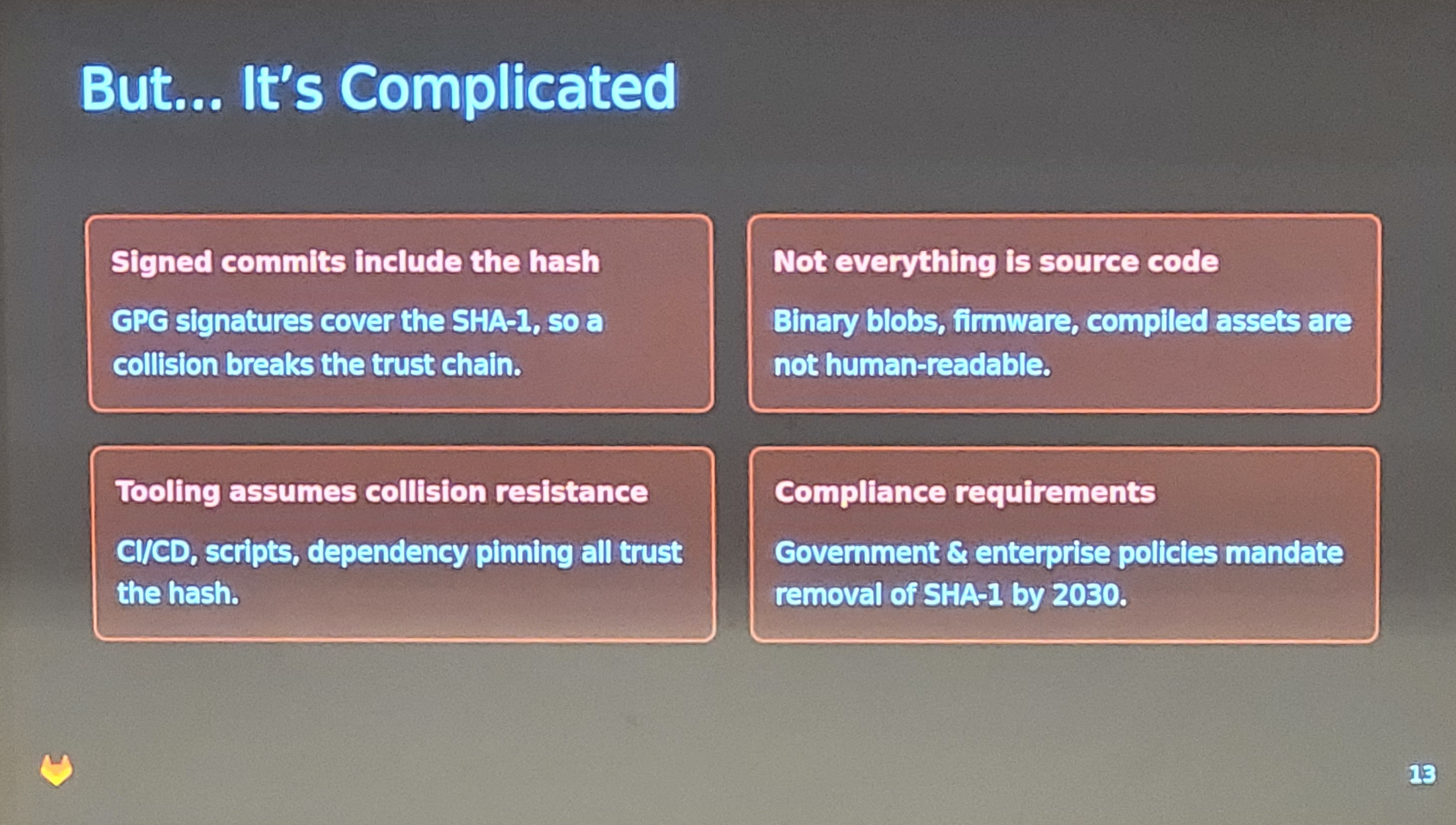

Historically, Git’s use of SHA-1 was about object integrity and identity, not “security features” in the everyday sense. But collisions and supply-chain realities have changed the stakes, so moving to SHA-256 is the responsible long-term direction.Hosting support reality check (early 2026)

This is still uneven — and that’s the whole point of pushing the default forward:

- Forgejo supports SHA-256 repositories (with caveats depending on version/features).

- GitLab supports creating SHA-256 projects as an experimental feature (you choose it at project creation).

- GitHub still doesn’t publicly offer SHA-256 repos as a supported feature; community threads exist, but nothing “flip the switch” official.

Why this matters: Git can’t unilaterally “finish” the transition. It becomes real when forges, CI checkouts, mirrors, and library integrations all behave correctly.

References storage : reftable

Classic Git ref storage is straightforward:

- loose refs: .git/refs/heads/<branch>

- tags: .git/refs/tags/<tag>

- plus packed-refs when refs are packed

This model is easy to understand… until you’re operating at serious scale: massive numbers of branches/tags, frequent updates, concurrency pressure, filesystem quirks, and the fun world of case-insensitive collisions and “which characters are allowed where”.

Patrick gave a server-side example on GitLab-scale installations: ref counts in the tens of millions are not theoretical anymore. At that point, the “simple” model turns into a bottleneck.

Enter reftable: a dedicated, portable, binary ref storage format built for performance and scalability (sorted refs, efficient lookups, range scans, compaction, etc.). It will also store the reflogs (a specific work will be done to improve usability and increase information)

You can try it easily:

git init --ref-format=reftable

reftable will help to scale to huge numbers of refs: faster lookups and iteration when you have tons of branches/tags (millions). It will provide also a more robust and portable storage for references: avoids filesystem edge cases (case-insensitive collisions, illegal characters, encoding quirks) by using a well-defined on-disk format. Performance is also a big point here when load is increasing. Reftable is designed for efficient updates/reads and improved concurrency compared to “one file per ref” and also heavy repacks operations.

If Git 3.0 pushes reftable as the default ref backend, it’s a quiet revolution: most developers will never think about it — but large hosting platforms and monorepo-heavy orgs will feel the difference immediately.

A native solution for large files in Git

Git still struggles with the “big binary assets” problem:

- every version of a large file is stored as a full blob history (and deltas don’t help much for many binary formats)

- cloning/pulling can get expensive fast

- compression is limited for already-compressed binaries

- LFS helps, but it’s not native Git, and it introduces extra moving parts

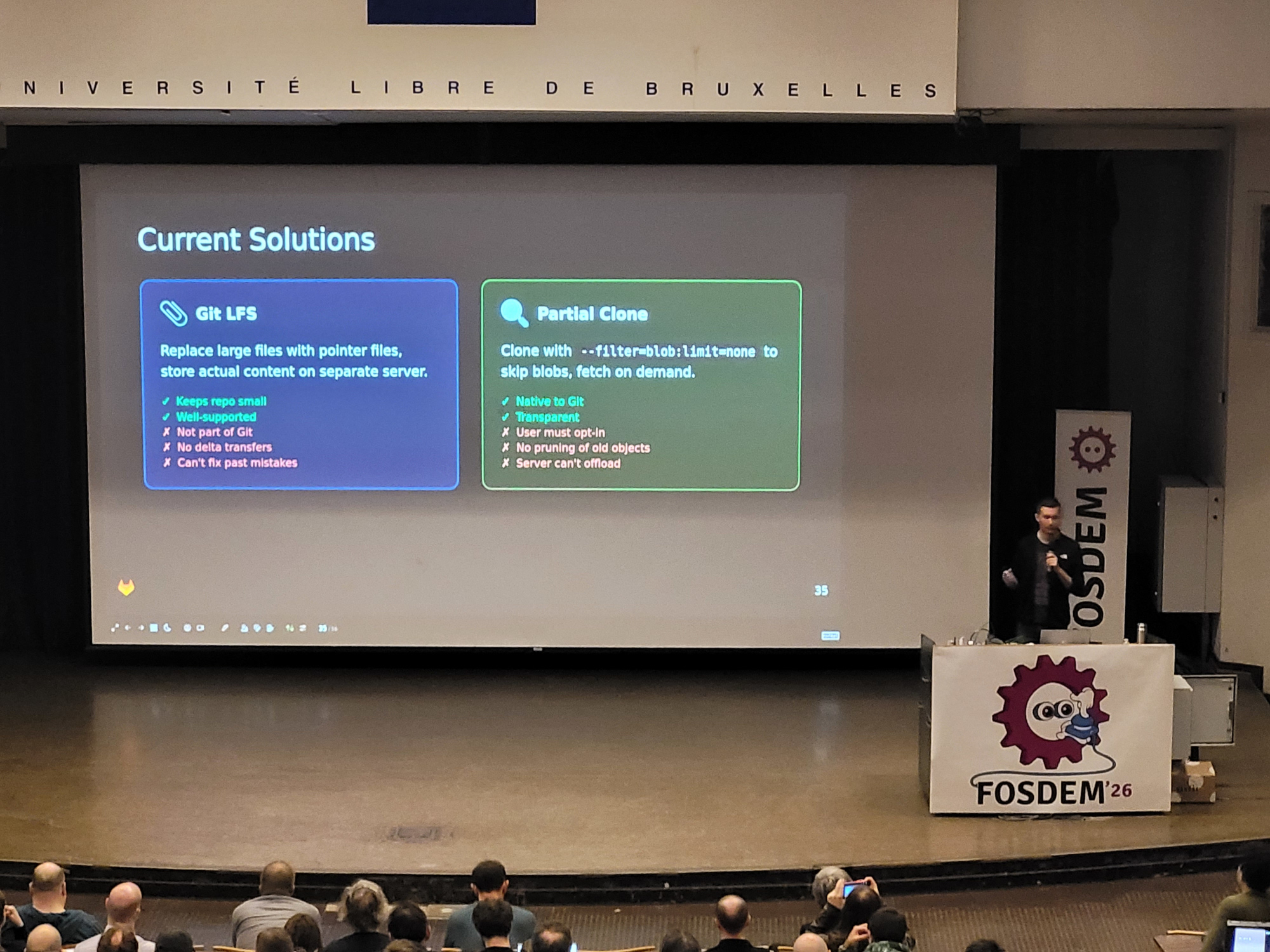

Git has made progress with partial clone, where you avoid downloading everything up front. But partial clone alone doesn’t make large binaries pleasant — it mainly makes them less catastrophic.

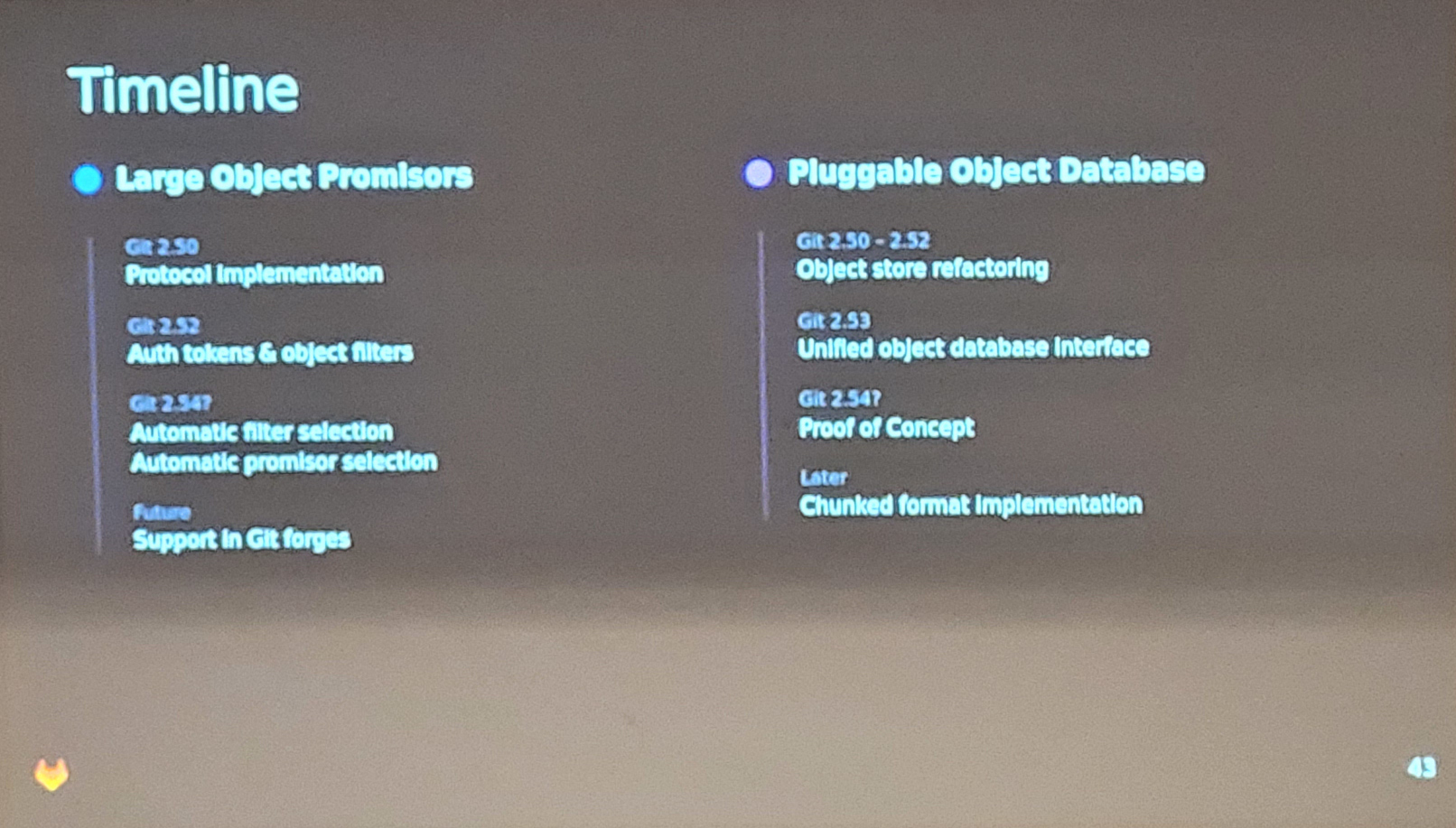

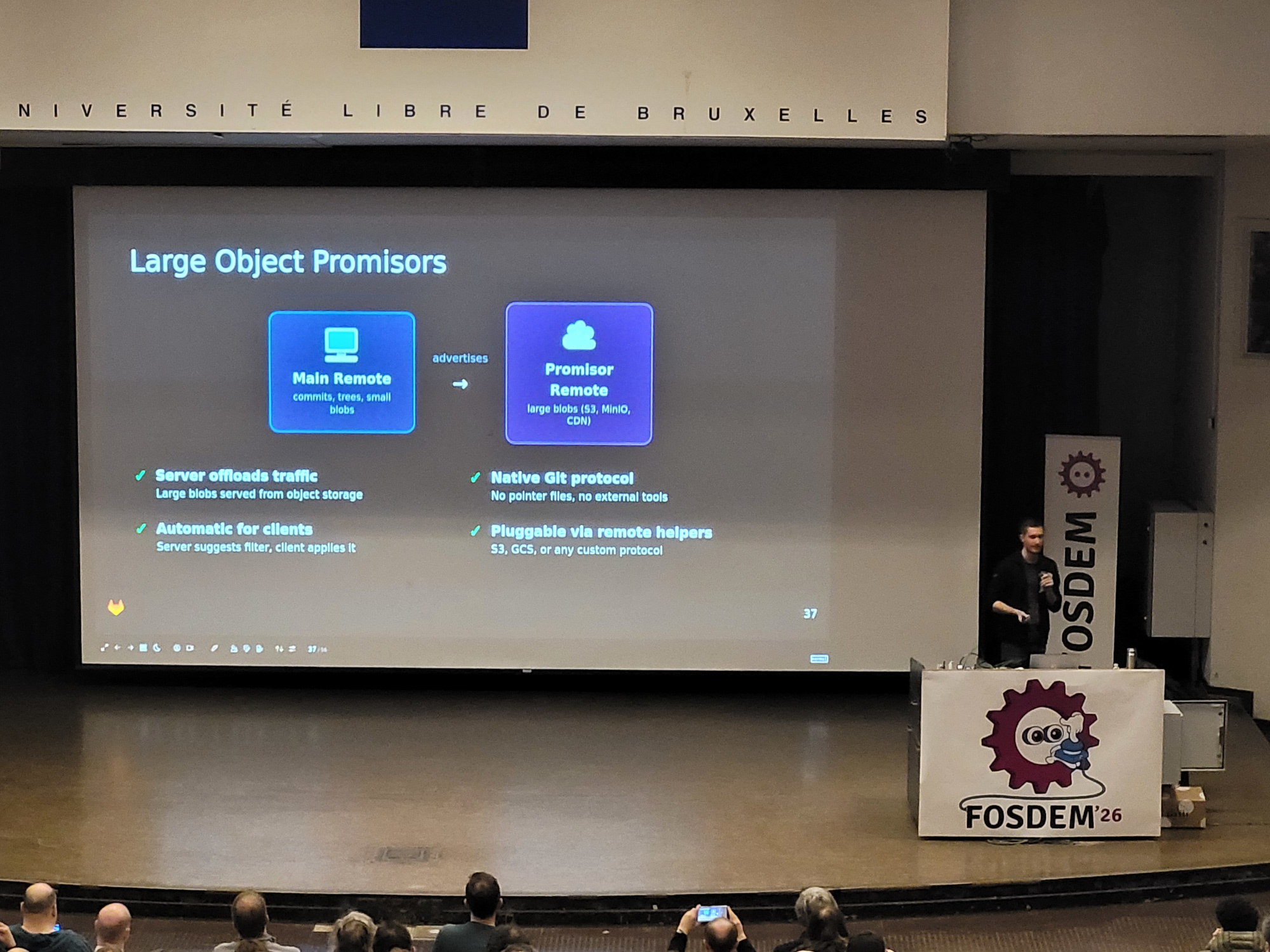

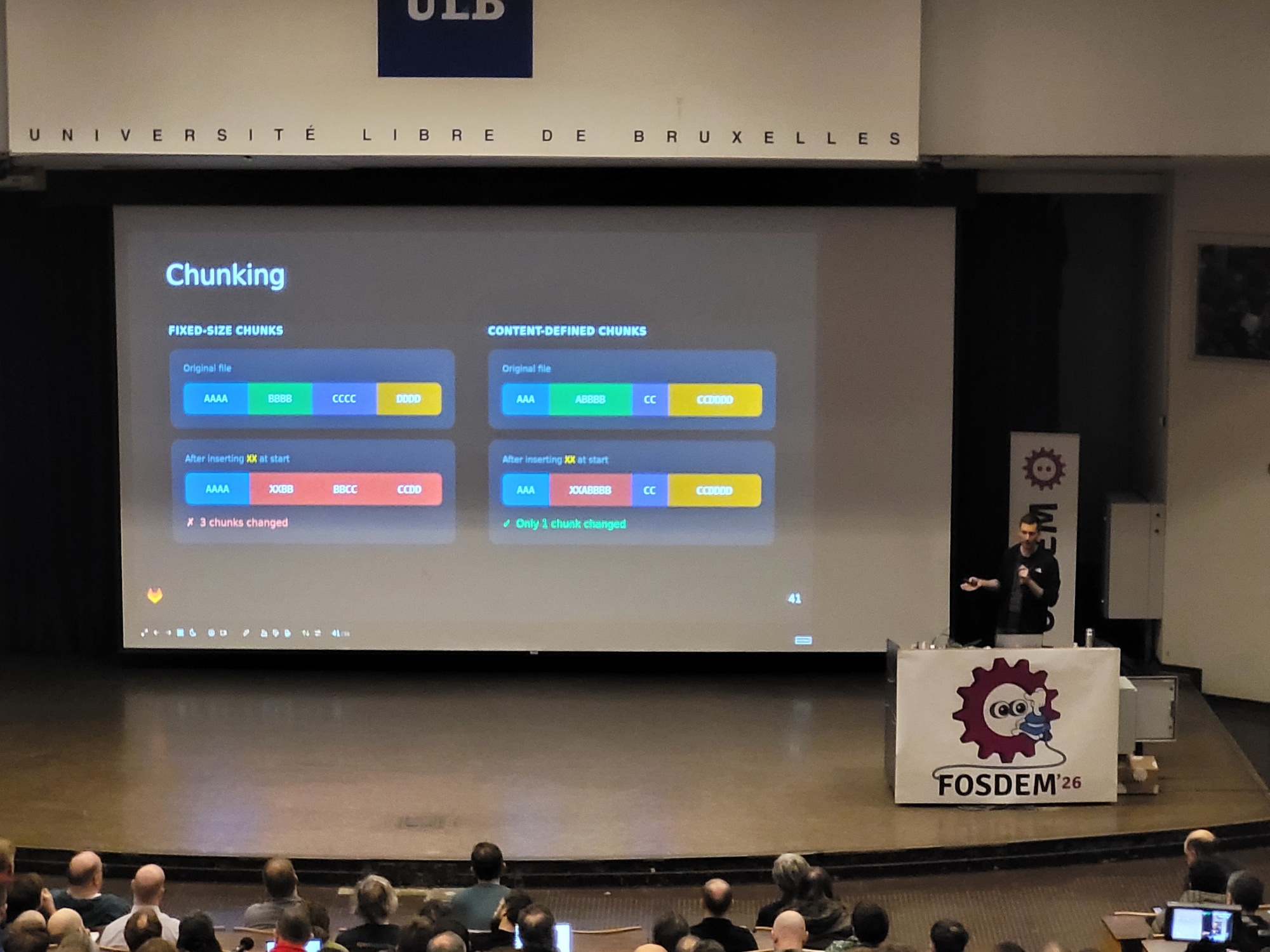

The direction Patrick highlighted is Large Object Promisors (LOP): the idea of a promisor remote that stores only large blobs, keeping the main repo lean, and fetching heavy objects on demand. The long-term vision includes more flexible object storage backends (“pluggable object databases”) and better deduplication (e.g., chunking).

Improve usability

For a long time, Git has had a reputation for being a footgun—powerful, but easy to misuse. Most of my trainees wouldn’t disagree… at least not before the training. The entry barrier is still high, and becoming autonomous often requires digging into Git’s plumbing and porcelain concepts just to perform everyday tasks confidently. That was also Patrick Steinhardt’s conclusion.

He mentioned the Jujutsu project: he had heard about it, took a first look, didn’t understand the mental model, and gave up. Later, he came back to it with a different mindset and realized there were valuable ideas worth borrowing—especially around usability. The key insight: focus on user intent and common workflows, not internal Git mechanics and low-level commands. Based on that approach, he started implementing a new git history command aimed at exposing frequent use cases directly.

Example: you want to rewrite a commit message that isn’t the latest one. Today, the “official” route is an interactive rebase—effective, but intimidating for many users. With this new approach, the intent becomes explicit:

git history reword <SHA-1>

git history reword <SHA-1>

Work is still in progress Patrick mentioned that git history could land around Git 2.54 if things go well (still tentative, since it’s under active development).